Understanding Seller Note Financing

What is a seller note?

A seller note, also commonly known as seller paper, seller financing, and seller debt, is a form of financing used in small company sale transactions whereby the seller agrees to receive a portion of the purchase price delayed over time. The buyer repays this remaining balance in a series of debt and interest payments.

A seller note is commonly used to bridge a gap between the amount a seller is seeking in a sale transaction and the amount a buyer is willing or able to pay.

Seller notes are also often used to fund buy/sell agreements between two partners in a business and when a seller elects to sell his or her company to their management team.

In this blog, we will describe the following scenarios:

- Where a Seller Note is Used

- How a Seller Note Works

- Different Types of Principal and Interest Payments on Seller Notes

- Benefits and Risks to the Seller

Where a Seller Note is Used

Bridge the Gap

Seller notes are a tool to bridge the gap between total financing available to a buyer, including the buyer’s equity, and the purchase price. In other words, seller notes bridge the value gap between the buyer and the seller.

More specifically, this value gap is the difference between the amount of capital a buyer can access and the total purchase price. If the buyer can only secure a bank loan that is 70% of the acquisition price and equity that is 20%, there may be a seller note issued that holds the remaining 10% of the price.

For example, if a buyer values a business at $9 million and the seller is seeking $10 million, a seller can help bridge the $1 million gap by issuing a seller note.

A seller note is not the only way the buyer can close the financing gap and meet the seller’s asking price. The buyer can also seek a larger bank loan, use more equity, or the buyer and seller could agree on an earnout.

First, the buyer could secure a larger bank loan to cover the gap with leverage. However, a bank may be hesitant to increase their loan size if the Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio is above the bank’s comfort level.

A Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio (“FCCR”) is calculated using the formula below, where “EBITDA” represents the company’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. “CAPEX” stands for the company’s capital expenditures, and the taxes referenced in this equation are cash taxes.

In small company transactions, most banks require a minimum FCCR of 1.2 to 1.25. That is, there needs to be enough EBITDA (or free cash) to pay a little over 1x the annual interest and principal payments on the loan.

The bank will enforce this requirement (also commonly called a covenant) to reduce the risk of the loan.

As a result, if there is a gap between the buyer’s available financing and the purchase price, a bank may not lend additional bank debt because it will bring the FCCR below the required level.

Another option for the buyer to bridge the financing gap is to use more equity.

However, equity is an expensive form of financing as it is the riskiest form of capital and a buyer may not have enough capital to fund a larger portion of the purchase price.

The buyer and seller could also bridge the financing gap via an earnout.

An earnout is similar to a seller note, in that the seller agrees to receive a portion of the purchase price over time. Most Earn-Outs are contingent on future performance – often based on future revenue, gross profit or EBITDA performance.

In exchange for accepting this risk, Earn-Outs often have a larger total value than seller notes. The value of the Earn-Out is driven solely on the future performance of the business. If the business does not perform, the seller may not be paid.

A seller note is a nice middle ground for the buyer and seller, providing benefits to both parties.

A seller note may be more desirable for the seller than an Earn-Out because the seller receives interest and principal payments, the seller note is senior to the equity, and most Earn-Outs are tied to future performance.

In comparison, the seller note becomes an obligation of the business and must be repaid according to its terms (more on this below).

Bridging a Valuation Gap

A seller note can be an effective way to bridge a gap between the price a buyer is willing to pay and the price a seller is willing to accept. If a buyer and seller are close, but not together, the seller note can be one way to make the transaction work for both parties.

The buyer can close the transaction without raising additional outside capital by receiving a seller note from the seller.

The seller eventually receives the total value of the purchase price when the seller note is repaid, as well as interest in the interim.

Fund a Buy-Sell Agreement

Seller notes are also often used to fund Buy-Sell Agreements between two partners.

A Buy-Sell agreement is a contract that states how a company’s shares will be valued, and subsequently purchased, when one partner decides to retire, passes away, or is unable to work.

If the remaining partner lacks the cash/equity to purchase the departing partners’ shares, the departing partner may issue a seller note to the remaining partner to “fund” the purchase.

Sell the Business to the Management Team

Similarly, when a Business owner seeks to sell his or her business to the management team, a seller note is often used to fund a portion or all of the purchase price. Often the management team does not have the equity required to fund the purchase price, or access to third party debt financing, so the seller will issue a seller note to the management team.

This allows the business owner to exit at the time that they want and receive the purchase price over time as the seller note is paid back.

How a Seller Note Works

Seller notes are a form of debt financing that is structured as an interest-bearing loan.

Seller notes are typically subordinated to any bank loans (commonly called “Senior Debt”) used to finance a transaction. If there is no Senior Debt, the seller note will not be subordinated.

Subordination is an important topic to understand in small company transactions.

In a typical acquisition including Senior Debt, seller notes, and equity, the Senior Debt has the highest priority for payment, followed by seller notes and then equity. As a result, there is more risk for a seller note than Senior Debt.

To offset this risk, seller notes often include a higher interest rate than Senior Debt.

In relation to the current market, most small company Senior Debt is repaid on a straight line basis over five years at an interest rate typically priced off of Prime. For example, Prime plus 1%. A typical seller note will mature over a similar period and carry an interest rate premium of 2% to 4%. For example, if senior debt is priced at 7%, a seller note might be at 10%. Further, the interest on a seller note may or may not be paid on a current basis through the maturity date. Instead, the interest may be deferred or accrued until the maturity date.

Deferred interest payments may be necessary in order to reduce the annual cash interest expense. Another way to reduce the annual expense is to back-load the principal payments.

This way the seller note does not affect the bank’s required FCCR or other covenants. Deferred interest and principal payments also improve the cash flow in the business– ensuring it has adequate cash flow to cover working capital requirements, other operating needs, and/or investment opportunities.

Different Types of Principal and Interest Payments on Seller Notes

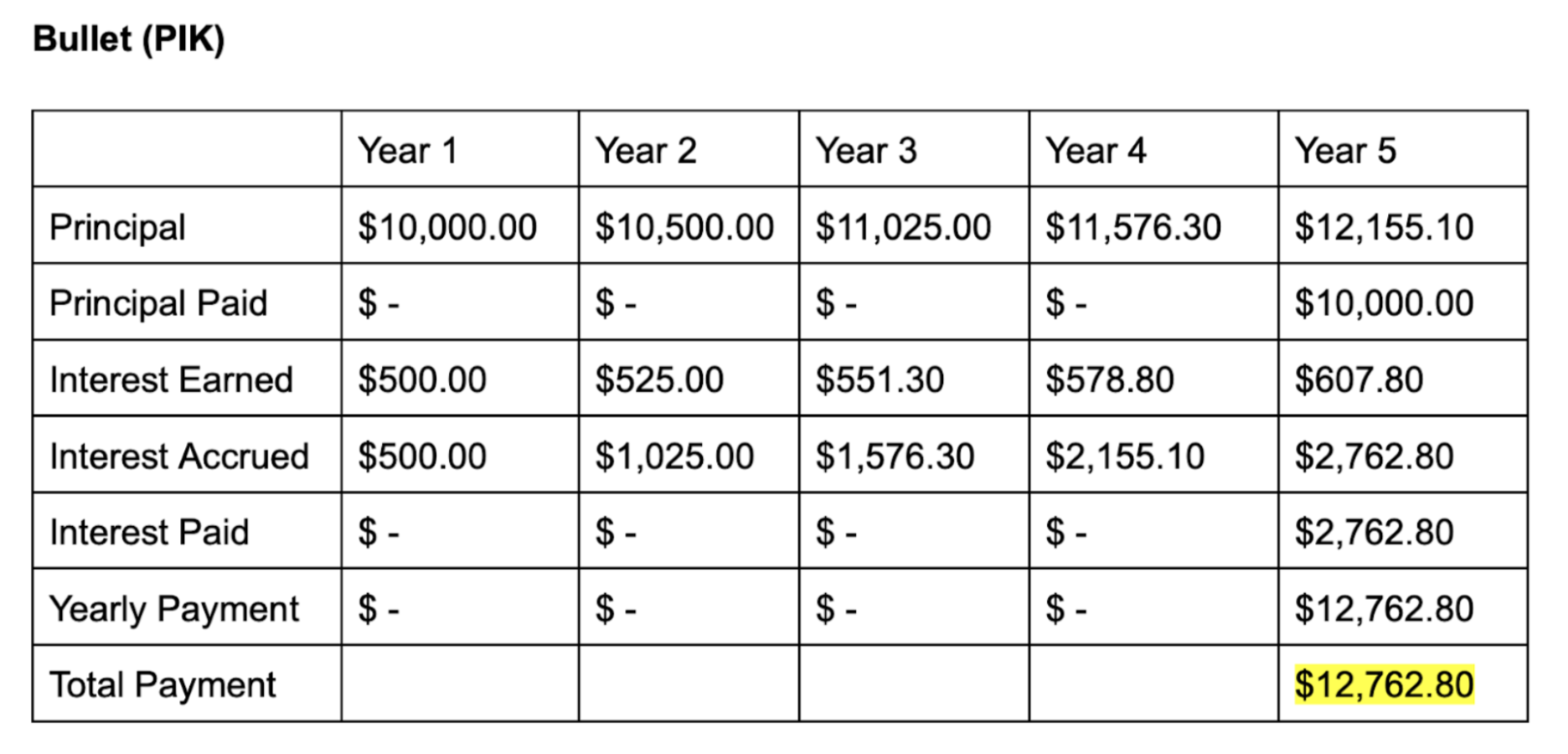

Bullet (PIK)

A bullet note describes a loan that pays all the principal at the maturity date.

Bullet loans can have deferred interest payments or recurring interest payments. Deferred interest payments are often called Payment in Kind, (“PIK”) interest. PIK interest is deferred and added to the principal balance of the seller note. The interest is then compounding over time.

For example, if the principal balance of the seller note is $10,000 with an annual PIK interest of 5%, the first-year interest expense is $500.

The second year would be $525 because the prior year’s interest payment is added to the principal.

The third year interest would be $551.3 and so forth. Each year, the PIK interest is added to the principal amount and is due at the maturity date.

Bullet (No PIK)

A bullet note can also include current interest payments rather than PIK interest payments. The original principal is still paid at maturity date, but the interest payments are made annually and do not compound. Using the same example above – a $10,000 seller note with 5% interest – the annual cash interest expense would be $500 each year. In the figure below, the interest is paid annually (or current) to the holder of the seller note.

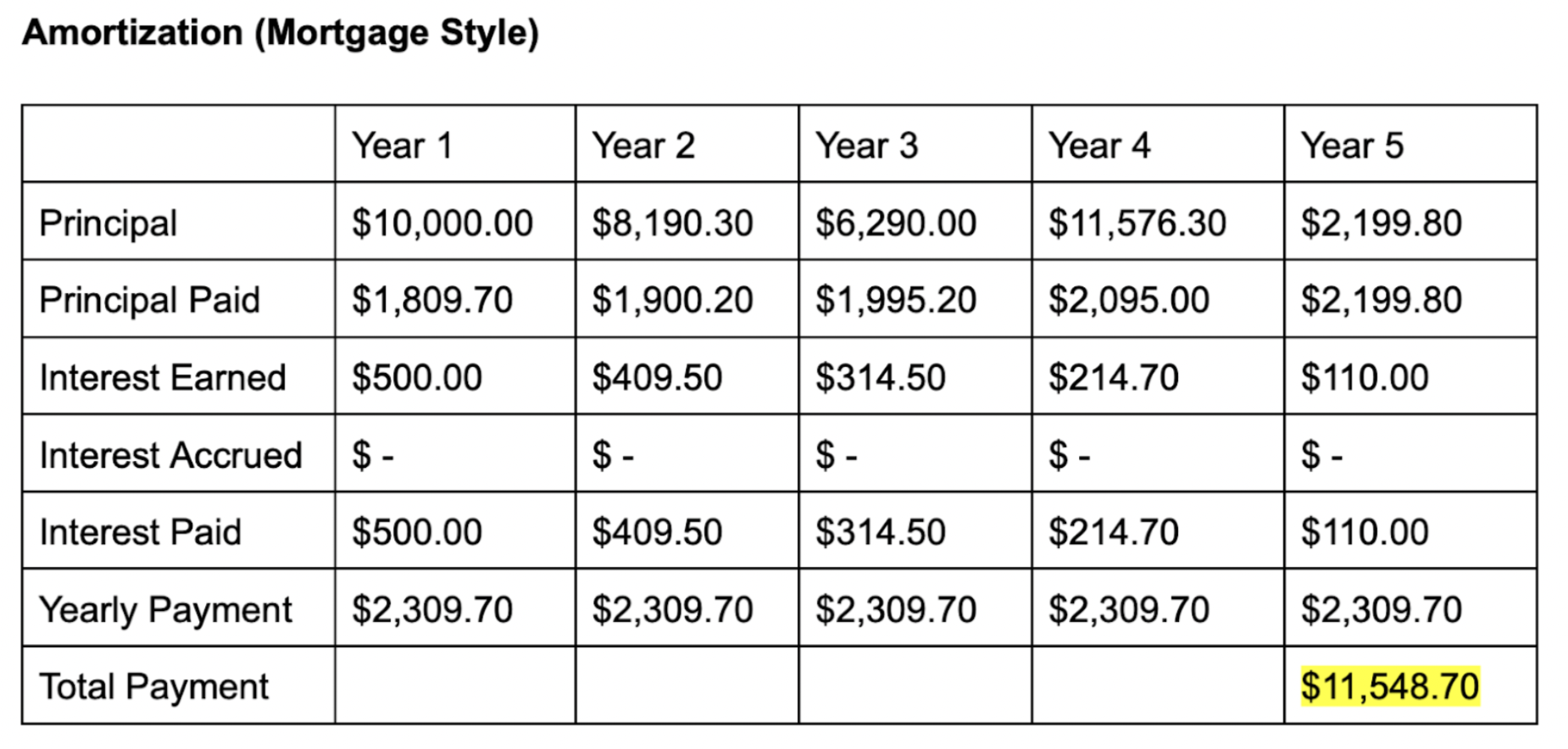

Amortization (Straight Line)

The most common method of repaying a bank loan is straight-line principal amortization over the term of the note with regular cash interest.

In simple terms, this means paying a portion of the principal and interest at every installment date. Each principal payment will be the same amount and the interest payment will decline over the life of the loan. Most bank loans with straight line amortization do not include deferred or PIK interest payments.

A straight line amortization note contrasts with a mortgage-style note. In a mortgage-style note, each payment amount is the same. While the interest portion decreases over the loan’s lifespan, the portion of principal paid increases.

Most commercial loans, including seller notes, rarely use this method of repayment.

Seller notes are most commonly structured as five-year bullet notes with current (no PIK) interest.

Benefits and Risks to the Seller

In small company transactions, the seller benefits from seller notes in many ways:

Benefits to the seller:

- Typically, a seller note allows for more flexibility in the acquisition and increases the probability of closing the transaction at a value acceptable to the seller.

- Receiving interest over the life of the loan will increase the total value received, and the interest is often much higher than what the seller could have received from an upfront cash payment sitting in a bank account.

- The seller knows the business well and can have confidence they will be repaid.

Where there are benefits to the seller, there are also risks.

Risks to the seller:

- Most seller notes are unsecured. That means if the business were to fail, and the seller note defaults, there may not be any collateral to cover the seller note. The future performance of the business is unknown and, like for any lender, this presents a risk that the seller note may not be repaid.

- Seller notes are subordinated to Senior Debt. If the business is not producing enough free cash to cover all of its obligations, then Senior Debt will be prioritized and the seller note may be impaired.

Conclusion

A seller note can be a great option to bridge a valuation or financing gap in a small company acquisition, to “fund” a buy/sell agreement, or to “fund” the sale of a business to a management team. Seller notes benefit both parties and can be structured to meet the unique requirements of the transaction.

However, it’s important to understand the structure as well as the benefits and risks of seller notes.

Do you have further questions about seller notes, or are you wondering how they might fit into the sale of your company? 1719 Partners is here to help— contact us today to get your questions answered.